‘Stahel style’ Industrial circular economy

«Currently, over 90% of the resources that are used globally do not return in the economic system. Only 9,1% of our society can be characterised as circular.»

(De Wit et al., 2018: The Circularity Gap Report 2018: An Analysis of the Circular State of the Global Economy)

«A nation-wide shift to a circular industrial economy would reduce greenhouse gas…emissions by 66 per cent….»

Wijkman, Anders og Skanberg, Kristian (2016) The Circular Economy and Benefits for Society Jobs and Climate Clear Winners in an Economy Based on Renewable Energy and Resource Efficiency

This note outlines a circular industrial economy, Stahel-style. It is part of what I have termed a real circular economy. As for the other parts -agriculture and biological circles- suffice to say here that the Community Wealth Building Model may act as a vehicle for operationalization of all parts.

Let’s first look at how Stahel compares the linear and the ‘conventional’ circular economy.

The linear economy: Stahel describes it as a ‘river-economy’. ‘A linear economy flows like a river, turning natural resources into base materials’ (e.g. cement, steel, plastics) and products for sale through a series of value-adding steps. ‘At the point of sale, ownership and liability for risks and waste pass to the buyer.’ [Stahel, W. (2016) The circular economy]. After use, goods exit the river as waste.

This is an economy where design for obsolescence along with bigger-better-faster-marketing results in large amounts of cheap goods. Success is measured in monetary streams that together make up a country’s gross domestic product,- without accounting for inequality and environmental consequences.

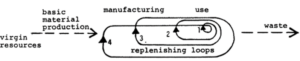

The conventional circular economy: In its conventional form, the circular economy starts at the point of sale, not at the design stage as (ideally) happens in the Performance Economy. Product life extension mean that goods produced by the linear economy are extended through various local/ regional loops, but eventually these goods will also end up as waste. So we are not talking about ‘closing the circle’; A loop is a curve that crosses over itself, like this:

In Stahel’s 1982-figure, the loops also crosses themselves when the goods turns to waste:

Source: Part of Fig C in Stahel (1982): Product-Life Factor

- Virgin Resources: Extracted through mining, oil drilling, logging, etc. [1]

- Basic Material Production: Cement, steel, plastics, etc.

[1] According to the UN resource panel, extraction of raw materials is responsible for half of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions (Ebba Boye [in Norwegian] (Klassekampen 10 juli 2019): Utleie kan bedre forbruk)

| Loop 1 | Reuse. The embedded energy and CO2 is almost completely retained |

|

Loop 2 |

Repair. (‘Loop 2’ in the figure above) |

|

Loop 3 |

Refabrication. Used goods or components are utilized for new production. May include technological/ /fashion upgrade. Potential for drastic reduction of energy & greenhouse gas emissions. |

|

Loop 4 |

Recycling. Utilize scrap/waste as locally available raw material. Recycling hardly influence the speed of material flows and goods through the economy. Recycling also competes with excavation of virgin resources because of high labor-costs for collection and sorting waste. Important is also the quality of the recycled product (‘downcycling’ or ‘upcycling’). |

Stahel’s three circular economy models and how they differ in terms of ownership and liability

1. The Loop Economy (see above figure) For each change in the loop, ownership-and liability also change. Profit is the primary motive, not preservation of products or materials.

2. The Lake Economy. Unlike the linear economy where the resources flows through and out of the river, resources are preserved as in a lake, for it not to be ‘drained’. Typical actors are not the producers themselves, but companies that wish to retain ownership as a way of preserving the capital that generates their income. An example is freight/transport companies that retains ownership, having a clear incentive to maintain (either themselves or through service providers) the quality and lifespan of vehicles, engines, tires and parts.

3. The Performance Economy is where services (‘results’) are sold instead of the goods themselves. Actors are typically the producers themselves, retaining not only ownership, but also liability for the goods, including all the materials that goes into the product. The circular economy, now starts with the very design of the products (ideally). In the best of cases, this enables resource recovery or materials all the way down to the level of atoms/molecyles (if necessary for complete resource recovery. And ‘in economic terms, recovered molecules are in price competition with virgin resources’ [Stahel 2019:41]). Furthermore, while the ‘Lake economy’ seeks to retain the values for goods and material, the performance economy seeks to increase them. To summarize:

- Economic actors sells performance (results/maximizing use) instead of goods.

- The actors retains ownership to and liability of goods and the materials that goes into them.

- Ideally the circuit of physical stocks will link with molecular circuits in order to recover pure atoms and molecules where products/materials can not readily be reused (think of the need to de-alloy metals or de-polymerize plastics, more generally to separate mixed material wastes).

- All costs associated with product liability, risk and waste are internalized, thereby giving a strong economic incentive to prevent waste and losses.

- Goods are sold as a service for as long as possible. Gains are maximized by using smart solutions, i.e. from (i) material and life sciences, ii) sufficiency solutions and (iii) system solutions.

- ‘Extended Producer Liability’-EPL (Stahel 2019) ensures an economic time perspective that is long-term. Note that EPL is far more extensive than EUs ‘Extended Producer Responsibility’ (EPR) , which allows responsibility to be delegated to third parties.

Source: Walter R. Stahel (2010) The Performance Economy. 2nd Edition and Walter R. Stahel (2019): Circular Economy-A users guide

Building upon and adding to Stahel’s framework

“The separation of power and responsibility is the fundamental problem of our current economic system… ..nobody ever really needs to take responsibility for the consequences of their actions.. …we need to reunite the possibility to act with the responsibility for the consequences of those actions. ”

(Rau og Oberhuber 2023:179,40, 52) [R&O] [1]

The below quote summarize R&O’s own explanation and their approach towards the solution:

«First of all, we must realize that ownership comes with accountability. Nowadays, all sorts of new possessions are forced upon us as consumers, for which we cannot carry any long-term responsibility.

As soon as we want to dispose of a product for whatever reason we are unable to bear responsibility for all the resources and materials it contains – let alone reuse or recycle them. As consumers we simply lack the means to do so. We can only solve this dilemma by changing our view on possession and ownership: by ensuring that we no longer have to own products in order to be able to use them.

We therefore have to steer toward a model in which producers remain responsible for their products, which means selling the functionality of a product as a service rather than the product itself.

If ownership of products remains with the producer, power and responsibility for the materials are no longer separated, in this case producers have an interest to extend the life of their products and if handled in the right way, components and materials remain available for future products and automatically incentivize manufacturers to opt for better design and material choices. Only then can we see to it that we use materials without consuming and exhausting them.

In this model, valuable raw materials no longer end up as waste, but eternally keep circulating within our (economic) system. This requires new revenue models, and consistently keeping track of the location of materials, by means of material passports..[This] applies to producers as well… we use most products (and therefore raw materials) for a short time only.. We will therefore have to ask ourselves where right of ownership of the raw materials themselves should lie, or else the producer will eventually be overburdened too.

In our view therefore, throughout the whole production chain – from the original source to the user at the end of the process – we should redefine to what extent ownership is functional or indispensable.

The consequence of that idea is that not only will products be sold as a service but materials will become a service as well. This way, a corresponding chain of value preservation is added to the existing chain of value creation..»

(ibid.: 5-6) [emphasize and text in brackets added]

In line with the above, R&O argues that stocks, infrastructure and products, all need to be designed and regarded as ‘material banks’ and equipped with materials passports to ensure continued use for future generations. Buildings are used as an illustration:

“[referring to R&O’s idea that] buildings should be seen as material banks, temporarily storing materials and conserving their value until they can be dismantled and reused elsewhere. Materials passports and registries can then be used to keep track of their identity and location so that they can eventually be recovered and continue to circulate within the economy.”

(ibid:: xi [Foreword by Dame Ellen MacArthur, text in brackets added])

[1] Thomas Rau and Sabine Oberhuber (2023): Material Matters. Developing for a Circular Economy.

Important references for what the undersigned has termed a Real Circular Economy are also Braungart og McDonough’s model for biological and technical nutrients and the latter’s concept of the ‘carbon economy’ (see also how these relates to Barry Commoner’s four laws of ecology).

‘But the circular economy can only be a reality for businesses if there are viable business models. Business models constitute the basic component of enterprises, being at the heart of value creation’ (Jonker et.al. 2018)[1]. Jonker and Faber followed up in 2021 with a comprehensive guide for the design and implementation of new circular business models. [2] Together with Haaker, they authored yet another paper in 2022, now as a whitepaper commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy. [3]

A new Business Model Template (BMT) designed for circular and collective business models was presented in the 2021- paper, differing substantially from the Business Model Canvas of Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010. [4] Maybe the biggest invention of this BMT is its focus on business model archetypes (platform, community-based and circular), which by itself or in combination, forms the basis for different business models.

Conclusion

I have in this note outlined key aspects of ‘a circular industrial economy, Stahel-style’, referred to Rau and Oberhuber (2023) building upon Stahel’s framework and to Jonker & Faber’s template for circular and collective business models. At the very beginning, the Community Wealth Building Model was referred to as a vehicle for operationalization of the industrial, agricultural and biological parts of what the undersigned have termed a Real Circular Economy.

While this ‘real circular economy’ is elaborated upon elsewhere, this is the takeaway here:

- Advanced concepts, tools and business models exists to replace the current linear economy.

- Much hinges on the political will to employ them.

- Particularly important is to level the playing field by putting a stop to the subsidising of elements that continue to incentivise linear economy business models. [5] Leveling the playing field would also require a tax shift: Labor is heavily taxed, while taxes on the use of natural resources are comparatively low. This is important, since reuse, use of secondary materials, refabrication and recycling associated with the circular economy are more labor intensive than that of the linear economy.

- One way to contribute to the leveling of the playing field, is to employ the Community Wealth Building Model, which through its combined anchor and procurement business model ( EU’s procurement directive is important here) can align local policies and business activities more in line with the concepts and tools described above.

Notes

[1] Jonker, J., Kothman, I., Faber, N. and Montenegro Navarro, N. (2018). Organising for the Circular Economy. A workbook for developing Circular Business Models. Doetinchem: OCF 2.0 Foundation.

[2] Jan Jonker , Niels Faber (2021): Organizing for Sustainability. A Guide to Developing New Business Models

[3] Jan Jonker, Niels Faber and Timber Haaker (2022) Quick Scan Circular Business Models Inspiration for organising value retention in loops. Whitepaper, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, The Netherlands.

[4] Osterwalder og Pigneur (2010): Business Model Generation

[5] “The amount of public money flowing into coal, oil and gas in 20 of the world’s biggest economies reached a record $1.4tn (£1.1tn) in 2022, according to the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) thinktank, even though world leaders agreed to phase out “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies at the Cop26 climate summit in Glasgow two years ago.” (Ajit Niranjan, 23 Aug 2023, the Guardian: G20 poured more than $1tn into fossil fuel subsidies despite Cop26 pledges – report)