Community Wealth Building (CWB): A road to Economic Democracy

Globalization’s ‘trickle down benefits’ were to bring prosperity for all. Instead, wealth has been extracted from local communities, making them loose of control over own development. To regain this control, we need economic democracy, locally rooted and with a spread of economic power. Only then will we get real democracy AND reduced inequality.

This implies a (re-) localization of the economy where a circular economy, municipalities and coops may work together -and reinforce each other- inspired by UK and USA’s experiences with the Community Wealth Building-model.

Economic Democracy

“Society long ago democratized government, but we have never democratized the economy.”

[Kelly and Howard 2019: xiii, see ref. below)

Already as far back as 1848, the English philosopher John Stuart Mill argued that a more democratic economy should be considered a condition for a more robust democratic society. More recently, Guinan and O’Neill argues that:

«If we want to live in democratic societies, then we need to have democratic institutions that allow communities to shape their local economies, and to exert real control over the way in which those local economies develop over time. Treating the economy as some kind of separate technocratic domain in which the central values of a democratic society somehow do not apply is no longer good enough. On the contrary, taking democracy seriously involves being prepared to extend it deep into economic life – including into the ownership of enterprise.»

Joe Guinan and Martin O’Neill (2020:47): The Case for Community Wealth Building

Related to this, is our schizofrenic approach to personal moral and business moral, succinctly illustrated by Joel Bakan:

«Few businesspeople would dispute that their decisions must be designed primarily to serve their company’s and its owners’ interests. As former Goodyear Tire CEO Sam Gibara said, “If you really did what you wanted to do that suits your personal thoughts and your personal priorities, you’d act differently. But as a CEO you cannot do that.»

Bakan, Joel. (2004:51): The Corporation: The pathological pursuit of profit and power

Kelly and Howard wish to break with the current ownership design where companies are “short-term, demand endless growth, measure success by profit and share price, externalize costs to the environment and are all too often amoral in decision-making“. The environmental movement is said to focus too much on technologies, having neglected the more fundamental question of ownership designs that drive corporate decisions – and to which ownership designs that support ethical, sustainable decisions.

In 2019, Kelly and Howard published the book ‘The Making of a Democratic Economy. Building Prosperity for the Many, Not Just the Few’. One of their principles for a democratic economy is to build and maintain local prosperity through locally rooted ownership. They point to the difference between investor-centered and democratically owned enterprises. In the first case, companies are seen as objects; “it is the perspective of owners who stand on the outside of a company, and who seek to extract wealth from it.” With democratic ownership, on the other hand, when the owners do their daily work in the company, the nature of the company changes: “Ownership is transformed from economic extraction to human belonging.”

Locally rooted ownership implies a (re-)localisation of the economy, a development away from chain power and investor-centred enterprises. Some will argue that this will weaken the economy of cities and local communities.

According to Michael Schuman, however, the author of the book ‘The Local Economy Solution’, a number of studies show that every dollar that moves from a nonlocal to a local business generates two to four times the increase in income, two to four times the jobs and two to four times the local taxes.

Community Wealth Building (CWB)

The connection betweenlocally rooted ownership, (re-) localisation of the economy and reduced inequality has beenoperationalized through the CWB model (2 min. video here),- a political and economic strategy known from (and tried out in) the USA and UK during the last decade. And as Tom Arthur of the Scottish Nationalist Party has emphasized, the CWB is not just for cities, it is an integrated approach to local and regional development.

CWB’s business model is based on a municipality’s/region’s expenditure on procurement, operation and maintenance. This particularly applies to ‘anchor institutions’:

«Cleveland’s [in Ohio, USA]’community wealth building’ project emphasises the role large institutions rooted in a municipality such as hospitals, airports, colleges, housing associations – and local authorities themselves – can play as ‘anchors’ around which regional economic ecosystems can stabilise and grow.

By allocating more of their spend budgets to local suppliers and producers, recruiting from the workforce on their doorsteps and incubating local businesses and community organisations, the anchors can keep wealth flowing in municipal economies.»

Justin Reynolds (Aug. 2017): Could Preston provide a new economic model for Britain’s cities?

Local cooperatives in particular have been supported to build up the said ecosystem. This is natural, given the cooperatives’ practice of cooperation among each other. Italy’s laws and incentives for cooperatives are also a source for inspiration.

For UK (before Brexit), the change in the EU procurement directive (in 2014) was important as it allowed tender with greater emphasis on social and environmental criteria. In fact, the English city of Preston worked with the EU along with ten other cities in Europe for ‘best practices’ procurement (Centre for Public Impact.org). This has made it easier to use progressive procurement and tendering, which another city in England, Manchester, says has resulted in savings of 85 million dollars over a ten-year period (Global network for public servants-Apolitical).

Still, it is Preston’s CWB model that have obtained most attention:

«Preston, England, once deemed the “suicide capital of England,” was inspired by Evergreen [USA] and built a more far-reaching model; in 2018 it was named by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and the London think tank Demos as the most improved city in the UK.

Preston has in turn inspired city leaders across England, Scotland, Wales, and as far away as Tanzania to reexamine what’s possible locally. Its success has led to the creation of a community wealth building unit in the UK Labour Party.

It’s not just leftists and Labour leaders who are interested. When the US Congress in 2018 passed new employee ownership legislation, it had bipartisan cosponsorship. In England, Conservative leader Edward Carpenter from Rochdale is looking at how he can build community wealth in his town.»

Marjorie Kelly and Ted Howard (2019:12): The Making of a Democratic Economy. Building Prosperity for the Many, Not Just the Few [emphasize and text in brackets added]

Platform Cooperatives and Digital Network Technologies

A tool well suited for the CWB-model, is digital network technologies. With Platform Cooperatives we may for example, ask: What if Uber was owned and run by the drivers? What if Airbnb was owned and managed by those who actually rent? Say welcome to Platform Cooperatives.

The formula is simple: combine the efficiency and reduced transaction costs of digital platforms with the horizontal ownership and democratic control that characterize worker-owned cooperatives.

One example is Up & Go Co-op (New York): «Up & Go relies on its own app to attract and book clients in the classic gig economy fashion. But while other booking services may pocket 20-50 cents on the dollar for lining up jobs, Up & Go cleaners, as co-owners of the co-op, keep 95 cents on the dollar and pay only 5 cents for booking.» [David Bollier 2021].

Local effectiveness of digital network technologies that also promote the circular economy is exemplified by ‘the Three River Farmers Alliance’ [USA]. Through a common digital platform, they have brought together various local producers in order to get enough volume for their own distribution, and for marketing, thus avoiding dependence on powerful intermediaries. [David Bollier 2018].

Circular economy and cities’ responsibility for their own supply chains

A further argument for (re-) localization of the economy is the need to reduce dependence on global supply chains. It has made us vulnerable to international crises and reduced our ability to manage our own finances, including prices of basic goods such as electricity and food.

Adding the economist Kate Raworth’s argument that cities must take responsibility for their own supply chains, this also becomes a principle for global responsibility for social and environmental sustainability, – and an agenda for action. This in turn can facilitate acceptance for reduced production and consumption, a prerequisite for a greater degree of circular economy. Wijkman and Skanberg, 2017, Club of Rome, has estimated that a national shift to a circular industrial economy would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 66% and increase the number of jobs by more than 4%.

Cities and local communities can lead the way. Progressive procurement and tendering processes under the auspices of CWB will enable the use of tools and business models developed by the nestors of the circular economy. While Walter Stahel is associated with the decisive Performance Economy-concept, William McDonaugh & Michael Braungart are known for the ‘cradle to cradle’ model as illustrated in this video. Thomas Rau explains in this video, how the cradle to cradle concept must be combined with Stahel’s Performance Economy model,- ‘fast forward’ to 7:16 min.

Why Locally anchored Cooperatives are instrumental in promoting Economic Democracy

Locally rooted cooperatives are a business-form well suited to promote economic democracy while at the same time serving to facilitate a (re)localization of the economy:

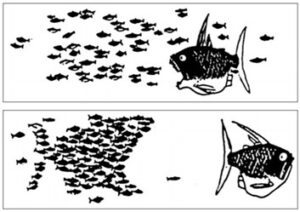

- Strong forces appears all-consuming. But cooperatives enables collective and self-interest to be aligned in standing up against these forces: When many people join together, individual risk is reduced, their negotiating position is strengthened, and – not least – the potential for real change increases (note that local cooperatives often collaborate on joint purchasing arrangements etc.) The below figure summarizes this:

Image credit: https://www.seedsforchange.org.uk/workersco-ops.pdf “This work is anti-copyright. Feel free to copy, adapt, and distribute it as long as the final work remains anti-copyright”.

- Cooperatives are the most important form of companies in which – traditionally speaking – the purely economic is subordinated to social principles and values, precisely because of the understanding that collective and personal benefit coincide. This in turn makes it possible for cooperatives to enshrine social, economic and environmental management responsibilities.

- Cooperatives have been central to political and economic strategies in many countries, not just to municipal authorities in the CWB model.

- In locally rooted cooperatives, the objectives of economic democracy, (re-)localization of the economy, reduced inequality and environmental responsibility come together (cooperatives must be locally rooted for members to identify with- and actively participate in managing the business). Add the principle of cooperation between cooperatives and that branching out to other local communities is more important than constant growth in one’s own company, which also implies another way of scaling.

Redistribution of the sources of Value Creation

CWB complements conventional redistribution. Now, there is the added focus on redistribution of the very sources of value creation. In other words, a (re-) localization of the economy that also becomes a democratic and more egalitarian economy:

«Community Wealth Building supports democratic collective ownership of the local economy through a range of institutions and policies.. [including] worker cooperatives, community land trusts, community development financial institutions, so-called ‘anchor institution’ procurement strategies, municipal and local public enterprises, and public and community banking.

[It] shift the position of individual citizens from being bystanders, who can only watch economic forces play out in their local communities, to active participants, who can collectively give some form and direction to the economic future of their local area.»

Joe Guinan and Martin O’Neill (2020:2, 47-48): The Case for Community Wealth Building

(Re-)localization of the economy must take place within the framework of a set of principles. If we consider Kelly and Howard’s principles for a democratic economy as a basis, this includes the common good as the first priority, democratic ownership design, building and maintaining local prosperity through locally rooted ownership and ethical finance for social and ecological benefit.

Conclusion

- Strong proponents for the status quo will fight a CWB model, even though it has received backing from both sides of the political spectrum in UK and the USA. But, for the over-whelming majority in cities and local communities, it will be a cause worth fighting for, one which integrates local wealth building, reduced inequality, environment and real democracy.

- For municipal authorities, it could represent a ‘solution multiplier’ – a coherent agenda that saves money and strengthen the local economy.

- «The starting place for CWB is that, in most communities, the resources, levers and tools already exist to begin creating a more equal, just and sustainable economy—you just have to know where and how to look for them. Whether it is local government, educational and school systems, the health service, cultural institutions and the non-profit sector, or public pension funds and other collective capital, the resources to build a more inclusive and democratic economy are all around you.» https://peoplesmomentum.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/CWB_MTM_11_April.pdf