There’s a System Approach to Democracy, Inequality & Climate

«Society long ago democratized government, but we have never democratized the economy.»

Marjorie Kelly and Ted Howard (2019: xiii): The Making of a Democratic Economy. Building Prosperity for the Many, Not Just the Few.

The front page introduced the issues of economic democracy, (re) location of the economy and a ‘real circular economy’. We found we needed a ‘solution multiplier’ to tackle several challenges at the same time – inequality, environment, climate – and the very prerequisite for real democracy; Economic Democracy. We identified the Community Wealth Building Model as such a multiplier. This page also serves as an overview, but a more elaborate one with more emphasize on tools for systems change.

Part I. About the need for System Change and Effective Tools

A. Shall we tackle Root Causes or treat Symptoms?

Shall we tackle problems where they actually originate (‘upstream’) or only treat symptoms (‘downstream’). What kind of advice would you like from your own doctor? Another illustration:

«You and a friend are having a picnic by the side of a river. Suddenly you hear a shout from the direction of the water—a child is drowning. Without thinking, you both dive in, grab the child, and swim to shore. Before you can recover, you hear another child cry for help. You and your friend jump back in the river to rescue her as well.

Then another struggling child drifts into sight . . . and another . . The two of you can barely keep up. Suddenly, you see your friend wading out of the water, seeming to leave you alone. “Where are you going?” you demand. Your friend answers, “I’m going upstream to tackle the guy who’s throwing all these kids in the water.»

Dan Heath (2020): Upstream. How to solve problems before they happen. [Who refer to this as ‘a public health parable (adapted from the original, which is commonly attributed to Irving Zola’]

B. Focus on Root Causes means focus on System Change

System change is not about single issues such as corruption or pollution from plastics. Rather, it’s about underlying structures that steers the economy, environment and society, not only in one area, but across the field. These are the structures we first have to identify, and then show alternatives for.

C. Why we need System Change; Family and Business Values are Incompatible

Important underlying structures in our market economy relates to how corporations act:

«Few businesspeople would dispute that their decisions must be designed primarily to serve their company’s and its owners’ interests. As former Goodyear Tire CEO Sam Gibara said, “If you really did what you wanted to do that suits your personal thoughts and your personal priorities, you’d act differently. But as a CEO you cannot do that.»

Bakan, Joel. (2004:51): The Corporation: The pathological pursuit of profit and power

The long-term view:

- Parents will be concerned with the future of their children 10-20-30 years on. This include concern for how the society can support their children’s education, health and environment.

The short-term view:

- In the market, especially for large corporations, it’s the quarterly result that counts, so a CEO cannot prioritize the long-term. Furthermore, to respond to expectations in the share market, turning a profi is not enough, it should always increase, or expected to do so.

- Preferably, the CEO should be schizophrenic: Apply one moral for business and another for the family. Unlimited growth, increased emissions and environmental destruction will affect the CEO’s own children and community. The CEO must still work to maximize the profit of the company and fight every regulation attempt that would lessen the damage to own children.

D. Why System Change has to include Spreading of Economic Power

(1) Spreading economic power is necessary to reduce Inequality: Some strategies based on Piketty’s research

Ridley-Duff and Bull (2019:367)[1] refer to Milton Friedman who argued that political power is much more difficult to distribute than economic power. If this is correct, then economic inequality may not best be fought through political institutions, at least not as a first priority. A more effective way to combat inequality would be to use collective property (‘group ownership’) with shared ownership and management of companies. ‘Distributed stakeholder ownership’ for example, may include all who contribute to the company’s income, i.e. investors, contractors, workers and consumers. The decisive factor is how the dividend is distributed between these.

“According to Piketty, any time period where the return from financial investment is higher than the overall growth in the economy will result in a systematic enrichment of the people and institutions responsible for the financial investments (at the expense of workers). For Piketty, the only way to eliminate structural inequality will be for the return to borrowers and to society to exceed that of investors.”

Ridley-Duff and Bull (2019:208)

In other words, ‘If returns to capital remain consistently higher than returns to labour, working people will continue to be impoverished and those with less bargaining power will be impoverished the quickest’ [Ridley-Duff and Bull 2019:367]. Ridley-Duff and Bull sums up four possible strategies for reversing this cycle: [2]

«

-

- The rate of return to capital is brought down to below the rate of return to labour (i.e. policies make sure that wages for workers rise faster than capital gains for investors).

-

- Excess profits are returned to borrowers (following the cooperative financial principle of the ‘patronage refund’) so that institutional financial returns are capped at 2%.

-

- Labour/consumers are allocated at least 50% of capital in non-state enterprises so they always participate in the returns to capital [i.e. follow FairShares/Cooperative principles].

-

- More capital is allocated as a ‘common pool resource’ to fund health, education and and welfare benefits (these enrich everyone in a community/company).

»

2022 World Inequality Report: Why reduced inequality is important also with regard to climate

«While the world’s poorest 50 per cent actually have very low emission levels, approximately 1.6 tonnes of CO2 per person per year, the richest ten per cent emit 31 tonnes and the richest one per cent 110 tonnes – per person!… Also many of us who do not belong to the richest, have a material consumption that produces many times greater emissions than the poorest 50 per cent. We must therefore also reduce our consumption and redistribute wealth to the poor.

In an interview with the well-known French economist, Thomas Piketty, reproduced in Klassekampen on 4 May 2022 [Norwegian daily], Piketty argues for measures that lead to such a redistribution. Political pressure must be created to ensure that the ten percent richest in society change their lifestyle and reduce their energy consumption.»

Translated from Norwegian article: Cato Aall og Gunnar Kvåle (Klassekampen 9. sep. 22: 18): Et grønt skifte kommer ikke med privatjet

(2) Spreading of economic power is necessary to maximize use of organizational forms optimal for social and environmental sustainability

From Piketty we derived the importance of collective business ownership to combat inequality. Spreading economic power also enables what Elinor Ostrom described as the optimal organization in terms of social and environmental sustainability. For our context, we can formulate this as follows:

Locally rooted and group-based ownership (i.e. shared ownership, not private) is the form of ownership that best matches social and environmental sustainability.

[Diffusion of economic power is implicit, both because ownership is shared and because local ownership involves the spread of ownership to many smaller economic units].

In 2009, Ostrom received the Swedish “Riksbank’s Prize in Economic Science in Memory of Alfred Nobel” – popularly called the ‘Nobel Prize in Economics’ for her research on the management of common resources through group membership (collective ownership rather than private ownership). Ostrom found that sustainability was strengthened in local group-based right-of-use systems, – assuming clear rules for use and management. This appears valid also for collective businesses in general- as long as they follow Ostrom’s spirit regarding said rules. The social & environmental argument for local and member-based business models can thus summarized:

When members have both rights and duties to maintain common resources, they will, instead of feeling alienated from the production they stand for, ‘re-establish the connection’ to this production. Internalization of social rights and protection of the environment thus becomes more likely.

Ideally, this is anchored in the statutes of the company/cooperative in a to ensure ‘generative ownership/ a regenerative economy’. We get generative ownership when ownership rights are integrated with financial, social and environmental management responsibilities (‘stewardship‘). On the environmental side, we talk about ‘regenerative design‘, best illustrated by the cradle to cradle principle which links to the objective of a slower circular economy:

“Growth makes a circular economy impossible, even if all raw materials were recycled and all recycling was 100% efficient. The amount of used material that can be recycled will always be smaller than the material needed for growth. To compensate for that, we have to continuously extract more resources..”

Kris De Decker (2018): How Circular is the Circular Economy?

It is not enough to circulate resources to complete the circuit [‘close the loop’]. We must slow the flow by reducing both production and consumption. Hence the term ‘slower circular economy’. [3]

(3) It is only with Economic Democracy we get Real Democracy

We have argued that the spread of economic power is desirable both with respect to inequality and the environment. Below, it is argued that spreading economic power is also desirable – indeed necessary – if we are to have a real and strong democracy. As for cooperatives, these must be locally rooted so that members can identify with and actively participate in managing the business. Spreading economic power thus requires focus on the local economy as well as democratization of capital, ownership and governance. The quotes below illustrate the need for democratization.

«Writing as long ago as 1848, in his Principles of Political Economy, John Stuart Mill argued that a more democratic economy could be seen as a precondition for a more robustly democratic society, as only if workers had the opportunity to exercise judgement and control at work would they be able to develop the kind of ‘active character’ on which our political institutions rely for their proper functioning.

If we want to live in democratic societies, then we need to have democratic institutions that allow communities to shape their local economies, and to exert real control over the way in which those local economies develop over time. Treating the economy as some kind of separate technocratic domain in which the central values of a democratic society somehow do not apply is no longer good enough. »

Joe Guinan and Martin O’Neill (2020:50,47): The Case for Community Wealth Building

“It’s impossible to have a truly democratic society when the institutions that comprise it are not democratic. People employed in undemocratic workplaces are drained of agency, which is bad for democracy and bad for society overall.”

Dave Darby (May 2020) The case for community wealth building: review

E. How to Enable the System Changes Required: Collective Action

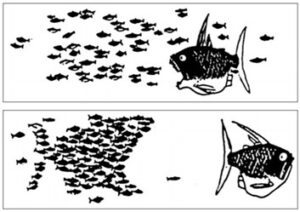

In order not to remain schizophrenic (see section C) we must adopt tools for system change. But what can give us real strength? The figure below illustrates why we must act collectively to stand against the strong predatory forces of today’s economy.

Image credit: https://www.seedsforchange.org.uk/workersco-ops.pdf “This work is anti-copyright. Feel free to copy, adapt, and distribute it as long as the final work remains anti-copyright”.

When many people join together, individual risk is reduced, their bargaining position is strengthened, and, not least, the potential for real change increases as collective and self-interest coincide.

F. The Cooperative Tradition is the best starting point for Collective Action and Business

[But ] “From attending broad public and societal interests, being an opposing force, ..[Norwegian cooperatives] act today in the same way and according to the same principles as privately owned actors [businesses]”

Bjørgulv Braanen (Commentary, Klassekampen, 29 April-21) [Norwegian daily] New spring for the cooperative idea [text in brackets added]

The cooperative tradition [i] [see endnote] is the best starting point because:

- Impact is best achieved through organization in larger groups

- (Traditional) cooperatives are the most important example of the purely economic being subordinated to social principles and values

- The principle of cooperation between cooperatives means that branching out to other local communities is more important than constant growth of one’s own company, which also implies another way of scaling

Nevertheless, the cooperatives must be revitalized because:

- They must be locally rooted so that the members can identify with and actively participate in managing the business.

- They must ensure that social, economic and environmental management (‘stewardship’) is strengthened in a way that actively reduces inequality and that helps tackle climate change.

- They must work so that growth can take place through budding to other regions.

G. Tools for System Change

The undersigned’s course plan for Cooperative Social Entrepreneurship identifies five tools for system change (in addition to economic, social and environmental management obligations laid down in the company’s articles of association):

-

Ownership Design/Spreading Ownership: “While the environmental movement has focused on physical technologies, it has neglected the more fundamental issue of ownership design that drives corporate decisions.” [4] New ownership design enables value reorientation and new forms of control (management), for example through Platform Cooperatives, Open Cooperatives and Multi-stakeholder Enterprises.

-

Democratization of Capital: Many locally rooted financial and organizational forms, known from England and the USA, provide opportunities to spread -and retain- capital in many more local hands, for example. through Community Shares, Credit Unions, Land Trusts, [House-] Building Societies, Civic-Public Partnerships and Cooperative-Municipal Partnerships.

-

Democratization of decision-making processes – including dedicated network solutions such as Loomio

-

Copyright replaced by Open source (ideas, program code, design)

-

Decentralization of the means of production / Democratization of production: Design Global, Manufacture Local (DGML).* Strengthens Local & Circular economy.

(*) Using ‘Computer-aided design’ (CAD), physical objects can be coded and read as digital information. Machines will then be able to use this information to control production processes such as wood milling, carving components in wood, metal and plastic, 3-D printing and much more. Open-source-available and/or mass-produced circuit boards as well as inexpensive electronic components such as sensors and ‘actuation’ components (which start/stop a process for an electrical article /machine) may then contribute to the completion of a wide perspective of products, – independent of traditional factories.

Physical objects – coded as information and shared freely on the web – can thus be transformed into local production in distant areas. Moving electrons in the form of copyright-free information around the world is far cheaper and produces far less emissions and use of energy than transporting coal, steel and plastic. It also encourages the use of local resources, circular economy, shorter value chains and strengthening of the local economy.

Part II. On Relocation of the Economy

(Re) Localising the Economy; Summary Rational and Linkages

- Globalization should bring prosperity for everyone, with effects that “trickle down” from the top of the social pyramid. Instead, values have been extracted from local communities and deprived them of control over their own development. To regain this control we need economic democracy. This must be locally rooted and enable a spreading of economic power. Only then will we get real democracy AND reduced inequality.

- Economic democracy requires (re)localization of the economy where more processes and businesses are locally or regionally based. This again requires the building up of Local Business Ownership– be it private, collective and public or state/private hybrid companies,- but all within the frame of democratic ownership. Democratic ownership design is where the environmental movement has failed: “[Focusing on technologies] it has neglected the more fundamental question of the ownership designs driving corporate decisions and of which ownership designs that are more supportive of ethical, sustainable decisions.” [Kelly and Howard (ibid:80)].

Building local, democratic ownership means that inequality no longer need to be addressed by redistribution alone. Democratic ownership design enables pre-distribution of the very sources of value creation.

- Thus enabled by a (re) location of the economy, economic democracy will in turn facilitate acceptance of a ‘slower circular economy’ (i.e. with reduced production and consumption). A slower circular economy will reduce our dependence on global supply chains and vulnerability to international crises. It will increase our ability to manage our own economy, including the prices of basic goods such as electricity and food.

- With Raworth’s argument that cities must take responsibility for their own supply chains, this also becomes a principle of global responsibility for social and environmental sustainability, – and an agenda for action. Along with CWB-strategies referred to below, such local economic policies can be a way of creating plans and models that prefigure large-scale alternatives.

- As noted in the front page of this website, ‘Community Wealth Building’ (CWB) brings these issues together and makes them operational. Note also the statement of Tom Arthur from the Scottish Nationalist Party saying that «community wealth building is not just for cities, it is an integrated approach to local and regional development, suitable for ventilation across Scotland.»

More references on the CWB-model are given later in this document.

Relocalization of the Economy; It’s significance for Reduction of Inequality

The below illustrates the need to relocate ‘back to the local’:

“Before Uber there was in Milan, Italy, in Lyon, France, two or three mini-cab companies that used to compete. The owner of that company would be worth 1 million or 2 million bucks. He was a rich guy in the local community. You had that in every city in Europe. They’ve all ceased to exist.

The same thing will happen all over the world. You will still have drivers. But that’s the most unskilled job in the line. The rest of the money will flow to Uber shareholders in Silicon Valley. So a huge chunk of the Italian GDP just moved to Silicon Valley.

With these platforms, the Valley has become like ancient Rome. It exerts tribute from all its provinces. The tribute is the fact that it owns these platform businesses. Every classified ad in Italy used to go into a town newspaper. Now it goes to Google. Pinterest will basically replace magazine sales. Now Uber dominates transport.”

He sees the same trend taking place with his permanent landlord, Airbnb, as it “will replace massive chunks of the boutique hotel industry and self-catering.” On the whole, Charlie observes that as sharing platforms expand, “the value flows to one of the places in the world that can produce tech platforms. So the global regional inequality is going to be unlike anything we’ve ever seen.”

Charlie Songhurst cited in Alex Ross (2017): The Industries of the Future.

Platform Cooperativism: Enabling Re-location, Economic Democracy & Democratic Ownership

What if Uber was owned and run by the drivers? What if Airbnb was owned and managed by those who actually rent? Say welcome to Platform Cooperatives. The formula is simple: combine the efficiency and reduced transaction costs of digital platforms with the horizontal ownership and democratic control that characterize worker-owned cooperatives.

Examples of successful cooperative platforms include Modo, a Canada-based car-sharing cooperative. Stocksy United, a artist owned cooperative that sells photographies online and Co-op Cabs (Canada). Cleaning is another example with Up & Go Co-op (New York):

«Up & Go relies on its own app to attract and book clients in the classic gig economy fashion. But while other booking services may pocket 20-50 cents on the dollar for lining up jobs, Up & Go cleaners, as co-owners of the co-op, keep 95 cents on the dollar and pay only 5 cents for booking.»

David Bollier (2021): The Commoner’s Catalog for Changemaking

Re-localization of the Economy for Social and Environmental Sustainability; The importance of cities

In the mid-1990s, Herbert Girardet estimated London’s ecological footprint, and found it to be 125 times the actual surface area of the city, in terms of the space it would need to produce itself the resources and services citizens consumed.

«The world’s major environmental problems can only be solved as part of the way we run our cities. ..Cities occupy only 2 per cent of the world’s land surface, but use some 75 per cent of the world’s resources, and release a similar percentage of wastes.»

[www.gdrc.org/uem/footprints/girardet.html]

Ede (2016) helps illustrate why relocation of the economy is a prerequisite for social and environmental sustainability:

«It is imperative that we understand the city as an ecosystem, acknowledging.. their impact beyond the physical city. These impacts..are typically not connected to an individual’s personal experience, and are rarely felt by more than the half of humanity who live in cities and towns. People in urban environments are rendered psychologically as well as spatially divorced from their dependence on nature, especially those who are caught up in a consumer culture that promotes abundance and has not yet encountered ecological limits.

..The needs of urban dwellers are also dependent on extensive external supply lines, which are a large contributor to carbon emissions.

Shipping is projected to be responsible for 17% of global emissions by 2050, and incredibly, both shipping and aviation are excluded from international climate change negotiations due to the difficulty of allocating emissions to one country.

..The circular economy approach can reduce demand for energy and materials and production of waste, [but only partly, see comments p.4] But if a city is not making things locally, does it truly have a circular economy? .. A true circular economy means relocalising production in our cities, needing to move less stuff, and making more of what we need, when and where we need it. »

Sharon Ede (2016): The real circular economy [emphasize and text in brackets added]

More on Tools, Business Models and Entrepreneurship for Relocalization of the Economy

(1) Experience from a decade of Community Wealth Building as a political and economic strategy.

2 min. video intro to Community Wealth Building (Center for Local Economic Strategies 2020)

«Community Wealth Building pursues a broad dispersal of the ownership of assets… Viewed in this way, community wealth building is economic system change, but starting at the local level.»

Joe Guinan and Martin O’Neill (2020:2-3): The Case for Community Wealth Building

«Preston, England, once deemed the “suicide capital of England,” was inspired by Evergreen [USA] and built a more far-reaching model; in 2018 it was named by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and the London think tank Demos as the most improved city in the UK. Preston has in turn inspired city leaders across England, Scotland, Wales, and as far away as Tanzania to reexamine what’s possible locally. Its success has led to the creation of a community wealth building unit in the UK Labour Party.

It’s not just leftists and Labour leaders who are interested. When the US Congress in 2018 passed new employee ownership legislation, it had bipartisan cosponsorship. In England, Conservative leader Edward Carpenter from Rochdale is looking at how he can build community wealth in his town.»

Marjorie Kelly and Ted Howard (2019:12): The Making of a Democratic Economy. Building Prosperity for the Many, Not Just the Few [emphasize and text in brackets added]

The starting place for CWB is that, in most communities, the resources, levers and tools already exist to begin creating a more equal, just and sustainable economy—you just have to know where and how to look for them.

Whether it is local government, educational and school systems, the health service, cultural institutions and the non-profit sector, or public pension funds and other collective capital, the resources to build a more inclusive and democratic economy are all around you.» Community wealth building. A toolkit for local councillors Prepared for People’s Momentum by The Democracy Collaborative, April 2022.

Furthermore, inequality is no longer being addressed by redistribution alone, but also through pre-distribution of the sources of value creation. Instead of sole reliance on redistribution, wealth and power-sharing can be rebuilt:

«Community Wealth Building is based upon economic interventions that seek to intervene not ‘after the fact’, in an attempt to redistribute the economic gains from a lopsided economic model, but by re-configuring the core institutional relationships of the economy in order to produce (…) more egalitarian outcomes as part of its routine operations and normal functioning. As such, it represents in microcosm a new approach to a more democratic economy.»

[Joe Guinan and Martin O’Neill (2020,5-6): The Case for Community Wealth Building]

[In sum] “..local economic policy can be a way of creating plans and models that prefigure large-scale alternatives.”

(Joe Guinan and Martin O’Neill (ibid.viii-ix)

(2) Economic democracy with social and environmental stewardship built-in

Stewardship may be ‘built-in’ through company articles. Here we can call upon the experience of several forms of democratic ownership, including worker owned companies, public companies, small and medium private companies as well as multi-stakeholder companies and platform cooperatives.

(3) Advancing distribution of the sources of value creation-, not just redistribution of income

Decentralization of the means of production makes this possible. Example: DGML (introduced in section G). Further reference:

«The process relies on people sharing innovative designs and knowledge globally on the Internet, while carrying out actual production locally. The method is being applied to everything from cars [Wikispeed] and farm equipment [Open Source Ecology /Farm Hack] to furniture [Opendesk], high-end scientific microscopes [e.g see this], modular houses [WikiHouse] [and electronics –Arduino]. For just the cost of local production-with no license fees or property restrictions, people can build these things themselves, adapting the designs as needed.»

David Bollier (2021): The Commoner’s Catalog for Changemaking – [emphasize and text in brackets added]

(4) Business Models for the Circular Economy

‘But the circular economy can only be a reality for businesses if there are viable business models. Business models constitute the basic component of enterprises, being at the heart of value creation’ (Jonker et.al. 2018) [1]. Jonker and Faber followed up in 2021 with a comprehensive guide for the design and implementation of new circular business models.[2] Together with Haaker, they authored yet another paper in 2022, now as a whitepaper commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy. [3]

[1] Jonker, J., Kothman, I., Faber, N. and Montenegro Navarro, N. (2018). Organising for the Circular Economy. A workbook for developing Circular Business Models. Doetinchem: OCF 2.0 Foundation.

[2] Jan Jonker , Niels Faber (2021): Organizing for Sustainability. A Guide to Developing New Business Models

[3] Jan Jonker, Niels Faber and Timber Haaker (2022) Quick Scan Circular Business Models Inspiration for organising value retention in loops. Whitepaper, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, The Netherlands.

In part, it builds upon the thinking summarized below.

Accenture (2014) [5] refers to the Product as a Service business model as an alternative to the traditional model of ‘buy and own’. Products are used by one or many customers through a lease or pay-for-use arrangement. This business model turns incentives for product durability and upgradability upside down, shifting them from volume to performance.’

“Manufacturers cease thinking of themselves as sellers of products and become, instead, deliverers of service, provided by long-lasting, upgradeable durables. Their goal is selling results rather than equipment, performance and satisfaction rather than motors, fans, plastics, or condensers.”

Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins, Hunter L Lovins, (1999:16): Natural Capitalism. Creating the next industrial revolution. Emphasize added.

De Decker (2018) sums up the relevance of this business model for the circular economy:

« In the circular economy, we would no longer own products, but would loan them. For example, a customer could pay not for lighting devices but for light, while the company remains the owner of the lighting devices and pays the electricity bill. A product thus becomes a service, which is believed to encourage businesses to improve the lifespan and recyclability of their products..»

(Kris De Decker (2018): How Circular is the Circular Economy?

According to Stahel (2013),[6] they internalise risk and waste costs. Moreover, the retention of ownership of goods and embedded resources creates corporate and national security of resources. And, according to Hawken et al. (1999) the service paradigm has other benefits as well:

“It increases employment, because when products are designed to be reincorporated into manufacturing cycles, waste declines, and demand for labor increases.”

Not only is local ownership important, but also democratic ownership as referred to in paragraph 2 above.

(5) Operationalizing Stewardship through re-configurated value chains

The EU public procurement rules allows certain room to maneuver. This may enable tenders that incentivize reconfiguration of value chains. An example of a re-configurated value chain, is Food Commons Fresno:

«[This is] a nonprofit trust that requires and stewards farmland and food-distribution infrastructure. The reconfigurated value-chain let’s farmers, ranchers, and fishers as well as distributors, processors, retailers, workers, consumers, and communities, share in the benefits that would otherwise be privatized by investors.»

David Bollier (2021): The Commoner’s Catalog for Changemaking – [text in brackets added]

(6) Entrepreneurship for the (re-) localization of the economy

Shuman’s ‘pollinator businesses’ illustrates what we mean by this type of entrepreneurship:

«In nature pollinators like bees, butterflies, or bats carry pollen from plant to plant, and they instinctively know that the intermixing of these pollens nourishes the entire ecosystem. Pollinator businesses similarly carry the best elements of one local business to another, thereby fertilizing all local businesses and creating a healthy entrepreneurial ecosystem.

..What distinguishes pollinator businesses is their acute sense of mission—to not only strengthen a particular local business for private profit but also strengthen the entire local business community.»

Michael Shuman (2015:16): The Local Economy Solution. How Innovative, Self-Financing “Pollinator” Enterprises Can Grow Jobs and Prosperity [emphasize added]

(7) Utilities that earn more money by selling less electricity

In the business model here referred to the economic incentives are turned upside down, also resulting in more local employment.

(8) The social sector: Upgrading volunteers and clients as coworkers translates into public savings

Community Wealth Building requires citizens taking on responsibilities and actively participate. That is true also for the social sector were this unique definition of coproduction have been used in English pilot projects:

a reciprocal relationship between professionals, people using services, their families and their neighbours. Professionals and citizens thus share power to plan and deliver support together. Where activities are coproduced in this way, both services and neighbourhoods become far more effective agents of change [7]

The professional’s knowledge can thereby be used as a catalyst with a significant potential for public savings. Mobile apps may further facilitate this type of coproduction. The undersigned’s nonprofit ‘Coopreneur’ may contribute through adoption of its app for pupil-to-pupil mentoring app. [8]

(9) Financing models for local economy-building

See Reference, section G, (‘Democratization of Capiital’)

Footnotes

[1] Rory Ridley-Duff and Mike Bull (2019): Understanding Social Enterprise Theory and Practice.

[2] Duff and Bull, ibid. emphasize and text in brackets added]. Sourced from ‘companion website for the third edition’ (for postgraduates: Crowdfunding and Investing, slide 10), https://study.sagepub.com/businessandmanagement/resources/ridley-duff-and-bull-understanding-social-enterprise-3e

[3] Se Paula Tejón Carbajal (2020): Slowing the circular economy

[4] [Marjorie Kelly and Ted Howard (2019:80) The Making of a Democratic Economy. Building Prosperity for the Many, Not Just the Few

[5] Accenture (2014): Circular Advantage Innovative Business Models and Technologies to Create Value in a World without Limits to Growth

[6] Stahel, W. (2013): Policy for material efficiency–sustainable taxation as a departure from the throwaway society.

[7] Adapted from Boyle, D and Harris, H (2009: 11) The Challenge of Co-production: how equal partnerships between professionals and the public are crucial to improving public services, nef/NESTA; London, UK, and Slay and Joe Penny (June 2014)

[8] Coopreneur is a nonprofit Norwegian Ltd – meaning no dividends, any profits are ploughed back into the company to further its ideal purpose. For the mentoring app, see https://mentor2mentor.top/

Endnotes

[i] About Cooperatives

Co-operatives are the only form of corporate entity with a clear entrepreneurial component where the subordination of the economic to the social is inherent in the logic of the organisation and is usually stipulated by law. (Levi and Pellegrin-Rescia 1997, p. 160)

Quoted in: [Tim Mazzarol, Sophie Reboud, Elena Mamouni Limnios, Delwyn Clark and Edward Elgar (ed.) (2014: 11): Research Handbook on Sustainable Co-operative Enterprise. Case Studies of Organisational Resilience in the Co-operative Business Model

This is reflected in the 7 international principles for cooperatives, summarized as follows:

(1) Voluntarily open membership (2) Democratic ownership- each member one vote [responsibility to members, not distant shareholders] (3) Member economic participation: Members contribute capital to the cooperative. (4) Autonomy and independence: If agreement(s) are made with other organizations or capital raised from external sources, democratic member control and autonomy must be retained.

5) Education, training and independence: Cooperatives provide education and training for their members, elected representatives, managers, and employees. (6) Cooperation between cooperatives: The cooperative movement is strengthened by working together through local, national, regional and international structures. (7) Concern for the local community: Members make policies to work for the sustainable development of their communities.

Presented by Coopreneur AS (a nonprofit Ltd, org no: 927 568 322)